|

|

|

Foot and Mouth Disease

The Disease in Missouri

|

|

In 1909 the Missouri Report of the

State

Veterinarian stated that Foot and Mouth disease appeared in several

of the northern and eastern states.

The killing and burning all of the diseased and exposed animals

was recommended as the only way to stop the disease.

Laws in Missouri made no provisions, whatsoever, for

controlling an outbreak of foot and mouth if one were to occur.

It was either luck or coincidence that an outbreak had not already

occurred in Missouri. In view of

the fact that the infection could spread into Missouri from other infected

states it was decided that the state must be

ready to 1) take effective charge of an outbreak at any time, 2) amend a

law to cover foot and mouth disease, and 3) to provide for the proper disposition

of affected animals. In 1914 a total of eighteen states had

known outbreaks of Foot and Mouth disease.

Officials in Missouri felt that an outbreak was eminent.

Many head of livestock were being killed in Missouri every day from the

stockyards in East St. Louis and Chicago. Inspectors in Missouri

were ordered to re-examine each lot of cattle that entered from a known

affected state. Missouri had entirely avoided Foot and Mouth Disease. However, until February 11, 1915 the state Board of Agriculture was without any funds to stop the introduction of Foot and Mouth into the state. On Feb. 11th the state legislature appropriated a budget of no more than $5,000 to be used in the prevention of an outbreak of Foot and Mouth. Within 48 hours the deputies living along the Kansas, Iowa, Illinois borders were activated to perform such work. Practically every road, bridge, and ferry along the Kansas and Iowa lines and down the Mississippi river to Cairo, Illinois were kept under careful guard. These deputies worked with help of the farmers along the lines to ensure that no infected or exposed animals entered the state until the threat was over. After the agents turned in their expenses the total cost of the operation was $743.

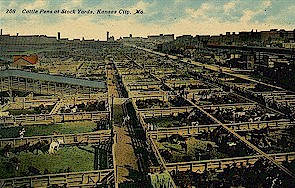

Kansas City Stockyards, ca. 1918 In 1917, the State Veterinarians office wrote a report containing information on Foot and Mouth Disease. The Stockyards in Illinois received a carload of hogs on January 21 from Christian county, Illinois, that had Foot and Mouth Disease. A re-inspection of all the cattle that came into Missouri from the Chicago Stockyards was ordered but no animals were found to be infected. Then on November 25 some cattle were received at the St. Joseph, Missouri, stockyards that later began showing symptoms that appeared to be Foot and Mouth. These cattle had been shipped to the Kansas City stockyards. Therefore nearly 200 lots of cattle and hogs that had been through these two stockyards were inspected. There were no animals infected with Foot and Mouth Disease. Some of the animals had contracted a similar virus that infected the mouth in the same manner, however this disease was not as virulent. It was not Foot and Mouth.The State Board of Agriculture of Missouri announced new Foot and Mouth regulations in 1919. It outlined the new Live Stock Indemnity Act which provided details on several diseases including Foot and Mouth disease. Section 714a of the Live Stock Indemnity act, enacted on May 13, 1919, stated that: "Cattle, hogs, sheep or goats found to be affected with or exposed to foot-and-mouth disease are to be quarantined by the State Veterinarian. The owner and the representative of the United States Department of Agriculture or a representative of the State Board of Agriculture will appraise the animals. In case of disagreement a third disinterested party is called in and a majority decision is final. The plan of this section is that the state and federal government shall each pay-one half of the whole value of the animal slaughtered, the cost of the burial and the cost of the disinfection of the premises. In short, the owner will get full value of everything." The last U. S. outbreak of the disease occurred in 1929, but it appears that Missouri has managed to always effectively avoid the problem. References:

|