|

|

|

After the Civil War

In 1860 there were about 12,913 head of native cattle in Missouri. However, the Civil War devastated Missouri's cattle industry. Six years later, at the end of the war, there were about the same number of cattle in the country. During the war, most of the cattle were neglected and soon after the war ended the cattle became more valuable. The roads to many markets were back open. When the war started almost all of the routes of transportation were shut down. Now people were hungry for beef and the cattlemen were ready to supply it.

The cattle that survived the Civil War were generally not well cared for. For example, at the end of the war in Crawford County, Missouri, it was reported that the average cow weighed about 375 pounds. An average 4 year old steer weighed around 475 lb. The steers were fattened on grass. However they said " the fault was in the genetics and not the grass" which indicates that there were probably no purebred cattle in that county then. The small size and poor quality of the cattle infers that these animals had been obtained from the cattle drives attempting to pass from Texas to St. Louis and other Missouri and Illinois markets.

It would usually take the cattle one to two months to recover from the winters. In Vernon County, it was reported that many cattle did not survive the harsh winters because of the poor nutrition and lack of availability of feed to the cattle. The lack of feed was because the farmers had to make a new start after the war. Many of the farms were small and the crops were not very abundant. Many people survived the winters by gathering the Indian calves from Oklahoma. Without these cattle from Oklahoma many of these people would have starved of cold backs and empty bellies, much like their own stock did.

People claimed that there were no dairy cattle in the region. Although they said the land was well suited for dairy cattle with tremendous amounts of grass and fresh water.

By 1866 somewhere around 260,000 head had crossed the Red river. The cattle market was booming and cattle were moving. Cattle were being gathered and driven to northern markets. The northern farmers had a lot to offer the cattle of Texas, such as large amounts of cheap feed and markets. Most of the cattle were fattened on corn before they were sent to slaughter. However as Texas cattle traffic increased in Missouri and Kansas and other adjoining states, the trouble and conflict also increased due to the "Texas Fever". In the year of 1860 the railroad had reached Sedalia Missouri, therefore cattlemen could divert their herds saving sixty miles.

The 1866 Missouri State Board of Agriculture Report included the following reports:

Vernon County. "Thousands of head of cattle are yearly driven from this county, in early spring, to the different points on the border, to be used as oxen in conveying the immigration to the vast west, or to supply the great demand made by government for transporting supplies. In summer and fall a constant stream of beef buyers are leaving with droves of fat cattle for St. Louis, or with poorer ones for other points in this State, Illinois or Ohio, to be fattened….They are raised to sell for oxen or beef, and not for dairy, the farmers permitting the calves to run with the cows, and not only have the advantage of all the milk, but of the fine grasses produced by our prairies, thereby adding greatly to their growth. In this way some of the finest two, three, and four year old beef is raised, which finds its way to the eastern markets. The farmers here have depended more upon their rich pastures than on their breeds of cattle; but those few who have tried the blooded stock have been able to sell at such advanced prices that others are dropping in, and I have no doubt a few years will entirely change our breeds….It is believed at the present prices near one hundred per cent, is made on the capital invested; certainly a great inducement to increase their flocks. "

Livington County. "The cattle raised by our farmers are mostly the common stock, which is believed to be the most profitable for milking purposes, notwithstanding a large number of grade Durhams (Shorthorns) are raised particularly for beef or market. For the last six years the larger proportion of our two and three year old steers has been purchased by men from Illinois, and there fatted for market. Our working oxen have found a good western market for crossing the plains to Idaho and other mining districts. The small amount of steers remaining, are fatted and find their way to St. Louis."

Webster County. "I have no data which to ascertain how many cattle have been driven to market. Previous to the war, which almost exterminated them, there were each year a great many driven to market; perhaps three thousand per annum-not more, however. The Durham's have been bred several years; have greatly degenerated for want of care and attention. No dairies, but excellent facilities for them offered by the abundant pasturage and pure springs."

Johnson County. "Twelve months ago the western part of this county had but few inhabitants; a large portion of the people had left during the war. What few remained had raised but little produce. Many of the fences around the farms had been burned and some of them Jayhawked. Some of the houses had been burned, and many others gone to wreck. But within that time a great radical change has taken place. I think we have at least three times the population we had one year ago, that is, in the western part of the county, and I am of opinion that the population has increased over fifty percent, taking the whole county together."

Very soon after the war cattle prices in Texas were as low as five dollars per head. However, the north was almost completely extinct of cattle. This shortage of cattle meant that the price of beef quickly rose to nearly ten times that amount. Some speculators saw an opportunity and began to buy cattle in preparation for driving them to northern markets.

The difficulty that they would encounter is that Missouri settlers remembered the disease problems they had had when Texas cattle had been driven through prior to the Civil War. Therefore the states of Missouri and Kansas made laws to attempt to regulate the droves of cattle being moved northward.

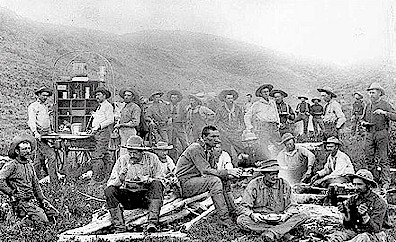

Chuck wagon dinner on the trail

As drovers moved their herds north they ran into lawmen and armed mobs in Southern Kansas and Missouri determined to keep their tick-infested cattle out of the area. The mobs might kill the drovers, or by dark of night stampede the cattle out of the country. However, many cattlemen were permitted to pass the mobs if they paid a high enough price that they saw fit.

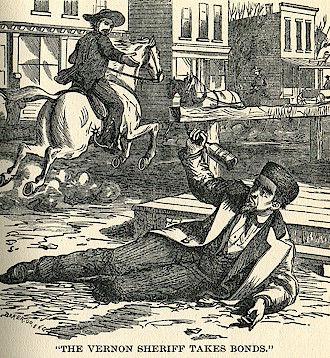

One account of R.D. Hunter who had gone to Texas and driven cattle northward into Vernon County, Missouri, is most interesting. Along with Mr. Hunter were several other drovers who along with their herds were "captured" by the Vernon County sheriff. The next day the drover came up with a scheme to escape. Telling the sheriff that he knew friends in Lamar who could post bail the two headed for Lamar. Meanwhile his companions under arrest started moving the cattle west back toward Kansas. When the sheriff and Mr. Hunter reached Lamar they went to the local tavern and commenced to drinking. After a while the sheriff was so indulged in liquor that he said Mr. Hunter had paid his bond and he left returning to all of his cattle and friends the next day.

By 1870, the cattle industry in Missouri had recovered somewhat. However, as cattle numbers increased, prices dropped. Here are prices reported in Lafayette county, Missouri in 1870:

|

Hemp |

$135.00 per ton |

|

Wheat |

$.80 per bushel |

|

Corn |

$.60 per bushel |

|

Oats |

$.40 per bushel |

|

Barley |

$1.00 per bushel |

|

Fat Cattle |

$.3-4 per pound |

|

Fat Hogs |

$.7-8 per pound |

![]() This

page was designed by Brad Evans and Aaron

Rieder

This

page was designed by Brad Evans and Aaron

Rieder

![]() For

more information, contact Lyndon

N. Irwin

For

more information, contact Lyndon

N. Irwin